In what seems to me to be a followup from a post in 2019 (Inner Earth? Scientists find mountains and plains 660 kilometers beneath Earth's surface), I found the following article fascinating and depressing:

Jan Lamprecht also called out this article:

http://hollowplanets.com/index.php/2020/06/24/pic-science-the-monstrous-blobs-near-earths-core-may-be-even-bigger-than-we-thought/

Also notice this article from last year:

Meet 'The Blobs': Two Continent-Size Mountains in Earth's Deep Mantle That Nobody Understands

Personally I can't decide whether to laugh or cry at the depravity of the author and researchers who are collecting this data.

They're clearly talking about structures inside of our planet that are massive: mountains and valleys that are much more enormous than anything we have on the surface... Yet they spout complete BS GARBAGE about it being magma. They have 0 (ZERO) evidence of this being the case, and yet they continue down this insane road of miseducation. At the very least they could simply say, "This is amazing and we don't know at all what these are or what they're composed of."

I feel it an utter shame and disingenuous to do what they're doing because it removes the mystique and allure of children and those that would be future researchers and scientists that might say "WOW! I want to figure this out and explore these unknown frontiers here within our own world!"

This outright attack on our children and future generations of scientists and the progress that we could see from such inspiration is a true crime against humanity.

For posterity's sake, I'll copy the article contents here:

#1:

The monstrous 'blobs' near Earth's core may be even bigger than we thought

By Brandon Specktor - Senior Writer 10 days ago

The mysterious 'blobs' near Earth's core just got a little bigger.

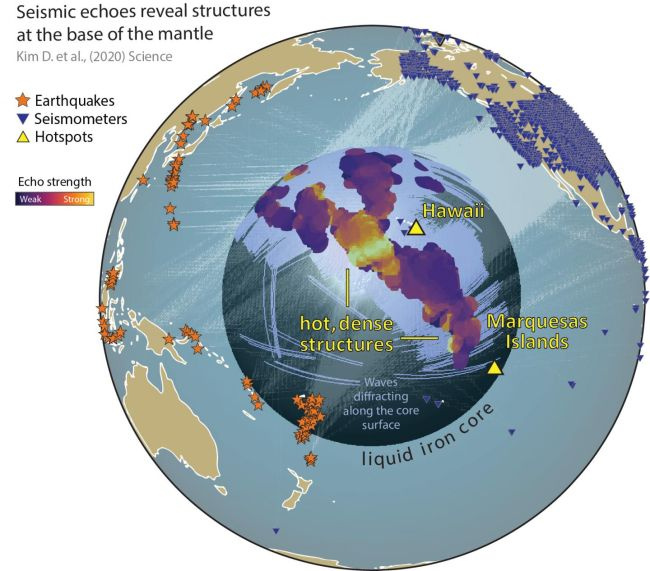

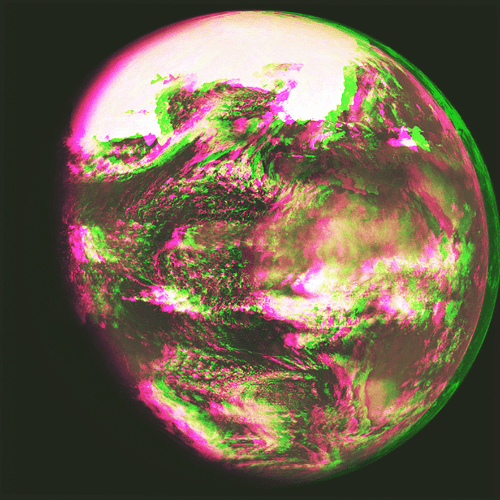

Earthquakes (stars) send seismic waves rippling through the planet. Seismometers (blue triangles) detect them on the other side. Thirty years of seismic data revealed where those seismic waves slowed down (purple and orange splotches), pointing to mysterious inner-Earth structures called ultralow-velocity zones. (Image: © Doyeon Kim/University of Maryland)Deep within Earth, where the solid mantle meets the molten outer core, strange continent-size blobs of hot rock jut out for hundreds of miles in every direction. These underground mountains go by many names: "thermo-chemical piles," "large low-shear velocity provinces" (LLSVPs), or sometimes just "the blobs."

Geologists don't know much about where these blobs came from or what they are, but they do know that they're gargantuan. The two biggest blobs, which sit deep below the Pacific Ocean and Africa, account for nearly 10% of the entire mantle's mass, one 2016 study found — and, if they sat on Earth's surface, the duo would each extend about 100 times higher than Mount Everest. However, new research suggests, even those lofty analogies may be underestimating just how big the blobs really are.

In a study published June 12 in the journal Science, researchers analyzed the seismic waves generated by earthquakes over nearly 30 years. They found several massive, never before-detected features along the edges of the Pacific blob.

"The structures we located are … thousands of kilometers across in scale," lead study author Doyeon Kim, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Maryland, told Live Science in an email. According to Kim, that's an order of magnitude larger than typical features found along the blob's edge.

Because the blobs live deep, deep in Earth's interior, geologists can only begin to understand their shape and size by looking at the seismic waves (sound waves generated by earthquakes) that travel through them. These hot, dense regions can slow incoming waves by up to 30% relative to the surrounding mantle; the hottest, slowest regions are known as ultralow-velocity zones (ULVZs), and they typically occur near the edges of the blobs, Kim said.

In their study, Kim and his colleagues created a new map of ULVZs below the Pacific Ocean using an algorithm called "the Sequencer," which was originally developed to find patterns in stellar radiation. With this algorithm, the team analyzed 7,000 seismograms, or measures of seismic waves, collected between 1990 and 2018, created by hundreds of earthquakes of magnitude 6.5 or greater. The earthquakes occurred in Asia and Oceania, the researchers wrote; but as their seismic waves shuddered across the globe, they passed clearly through the Pacific Ocean mantle blob before reaching seismometers in the United States.

The algorithm revealed enormous sections of ULVZs never detected before, including a blobby region below the Marquesas Islands in the South Pacific Ocean, which measured more than 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) across. The Sequencer also showed that a segment of the blob deep below the Hawaiian Islands is considerably larger than previously thought.

"By looking at thousands of core-mantle boundary [seismograms] at once, instead of focusing on a few at a time, we have gotten a totally new perspective," Kim said in a statement.

The enormous size of these structures suggests that blobs along the core-mantle boundary — and particularly the hottest, densest ULVZs — are probably more widespread than previous research indicates. What's more, Kim added, the fact that these large zones lurk near known volcanic hotspots could also reveal some clues about their impact on Earth's geology.

It's possible, for example, that ULVZs deep down in the mantle could feed into the large "plumes" of hot rock in the upper mantle that create volcanic hot spots on the surface, Kim said. Those mantle plumes might "suck on" the melty material collected in ULVZs and pull it upward, which could explain why the largest ULVZs are located deep under volcanic island chains like the Hawaiian and Marquesas islands.

That's just one theory, Kim said; even with algorithms designed to pierce the void of space, the mysteries near the center of the Earth remain just as murky as ever.

"In short, everything is unsure at the moment," Kim said, "but this is what makes our field of study so exciting."

#2:

Meet 'The Blobs': Two Continent-Size Mountains in Earth's Deep Mantle That Nobody Understands

By Brandon Specktor March 07, 2019

About halfway between your feet and the center of Earth, two continent-size mountains of hot, compressed rock pierce the gut of the planet — and scientists know almost nothing about them.

Technically, these mysterious hunks of rock are called "large low-shear-velocity provinces" (LLSVPs), because seismic waves shuddering through Earth always slow down when passing through these structures.

A mesmerizing image, featured in an article on Eos (the official news site of the American Geophysical Union, or AGU), gives us one of the most detailed views yet of these rocky anomalies — which most scientists simply call "the blobs." [Earth's 8 Biggest Mysteries]

Geophysicists have known about the blobs since the 1970s but aren't much closer to understanding them today.

"They're among the largest things inside the Earth," University of Maryland geologist Ved Lekic told Eos reporter Jenessa Duncombe, "and yet we literally don't know what they are, where they came from, how long they've been around, or what they do."

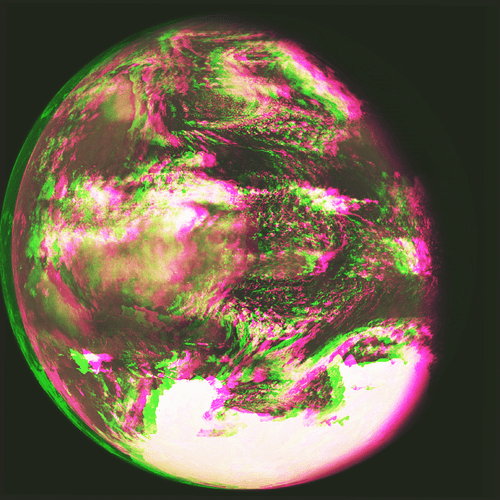

This much is evident: The blobs begin thousands of miles below Earth's surface, where the planet's rocky lower mantle meets the molten outer core. One blob lurks deep below the Pacific Ocean, the other beneath Africa and parts of the Atlantic. Both are massive, stabbing up about halfway through the mantle and measuring as long as continents. According to Duncombe, each blob stretches about 100 times higher than Mount Everest; if they sat on the planet's surface, the International Space Station would have to navigate around them.

To get a better sense of their shape and scale, take a look at the stunning 3D map of the blobs that Lekic and University of Cambridge seismologist Sanne Cottaar created in 2016 (shown above). The blobs' vast, cascading plains have been likened to mountains of sand or interconnected pits of gravel, Duncombe wrote, but whether they're lower- or higher-density than the surrounding mantle remains a point of contention among scientists.

Equally mysterious is how, if at all, the blobs affect geological functions such as plate tectonics and volcanism. A more recent map of the structures, presented by University of Oxford doctoral student Maria Tsekhmistrenko at the 2018 annual meeting of the AGU, suggests that the tips of the blobs might branch into plumes of hot material that brush up against volcanic hotspots just below Earth's surface. What does this mean? Nobody knows. It may take many more decades to better understand the enigma near the heart of our planet. Luckily, the blobs don't seem to be going anywhere.

You can read Duncombe's article here.